One of my favourite pithy quotes is ‘Tradition is just peer pressure from dead people’. When you start looking at some of the things we ‘just do’, you start asking yourself ‘why, exactly?’

For example, when you attend a wedding, you’ll see the bride standing on the groom’s left. This is so that he can use his sword to fight off her family as he carries away from the town over his left shoulder.

Another example is the story that’s often told about how the distance between railway tracks is related to the width of a horse’s ass.

There’s a similar thing that happens in multichannel audio systems. When people ask me what I would recommend for loudspeakers when building a multichannel (or ‘surround’) system, I always start with the ITU’s Recommendation BS.775 which says that you should use matching loudspeakers all-round. Of course, almost no one does this, so the next best thing is to say something like the following:

- use big loudspeakers for your Left Front and Right Front

- use smaller (but matched) loudspeakers for your surround channels (including back and height channels)

- make some intelligent choice about your Centre Front loudspeaker

(which is not terribly helpful, but there are many issues to consider when thinking about your centre front loudspeaker)

This raises a question:

‘Why is it okay to use smaller, less capable loudspeakers for the surround channels?’

The simple answer to this is that for most materials, there isn’t as much signal in the surround channels, and there’s certainly less low-frequency, high-level content.

However, let’s keep asking questions:

‘Why isn’t there more content (in terms of both bandwidth and level) in the surround and height channels?’

The answer to this is that surround sound (like stereo, which is in effect the same thing) originated with movies. The first big blockbuster that was released in Dolby Stereo (later re-branded as Dolby Surround) was Star Wars in 1977 or so. Dolby Stereo was a 4-2-4 ‘encoding’ system that relied heavily on M-S encoding and decoding. If I over-simplify this a little, then the basic idea was:

- The Centre channel was sent to both the Left and Right channels on the film

- Left channel was sent to Left

- Right channel was sent to Right

- The Surround channel (there was only one) was mixed into the Left and Right channels in opposite polarity (aka ‘out of phase’)

So, the re-recording engineer (the film world’s version of a recording engineer) mixed in a 4-channel world: Left, Right, Centre, and Surround, but the film only contained two channels: Left Total and Right Total (with the Centre and Surround content mixed in them).

When the film was shown in a theatre with a Dolby Stereo decoder, the two channels on the film were ‘decoded’ to the original four channels and send out to the loudspeakers in the cinema.

This was a great concept based on an old idea, since M-S processing was part of Blumlein’s original patent for stereo back in 1931. When you’re looking at a two-channel stereo signal, you can think of it as independent Left and Right channels. However, usually, if you look at the content, the two channels contain related information. For example, the lead vocal of almost every pop tune is identical in the Left and Right channels so that its phantom image appears in the centre.

So, another way of thinking of the same two-channel stereo signal is by considering the two channels as

- ‘M’ (for Mid or Mono, depending on which book you read):

the signal that is identical in the Left and Right - ‘S’ (for Side or Stereo):

the signal that is identical except in opposite polarity in the Left and Right

For example, FM Stereo is not sent as Left and Right channels, it’s sent as M and S channels. There’s less bandwidth and less level in the S component, so when you lose the FM signal to your antenna, the first thing to go is the S, and you’re left with a Mono radio station.

Wait… there’s that ‘less bandwidth and less level in the S component’ again – just like what I said above about the surround channels in a surround system.

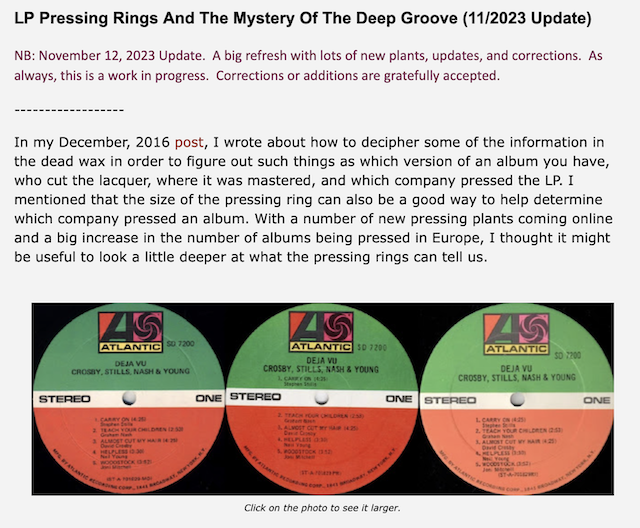

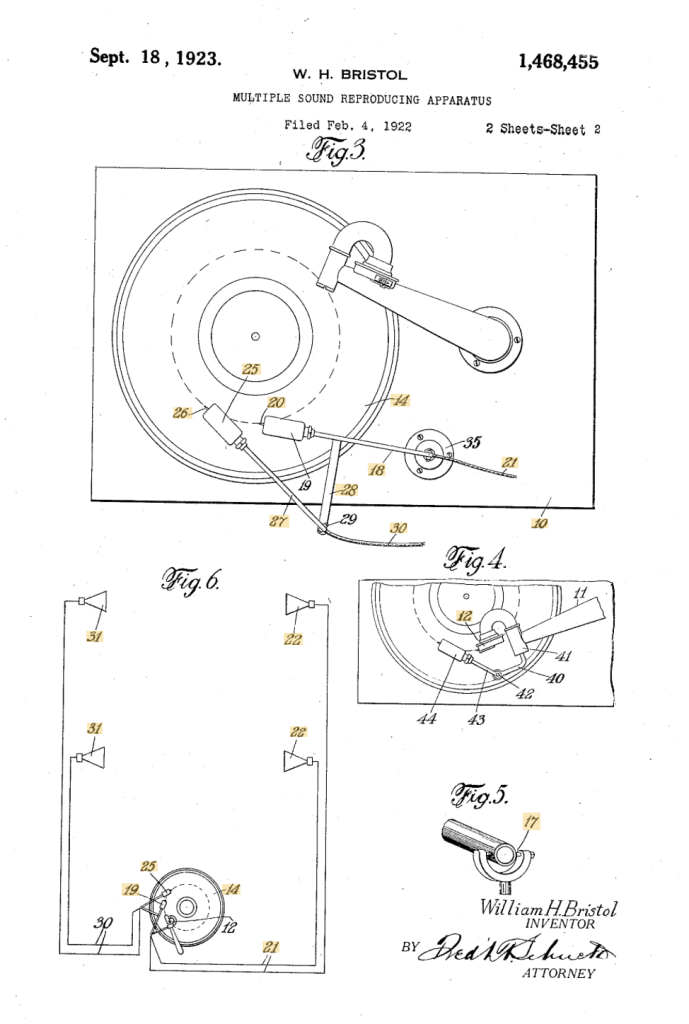

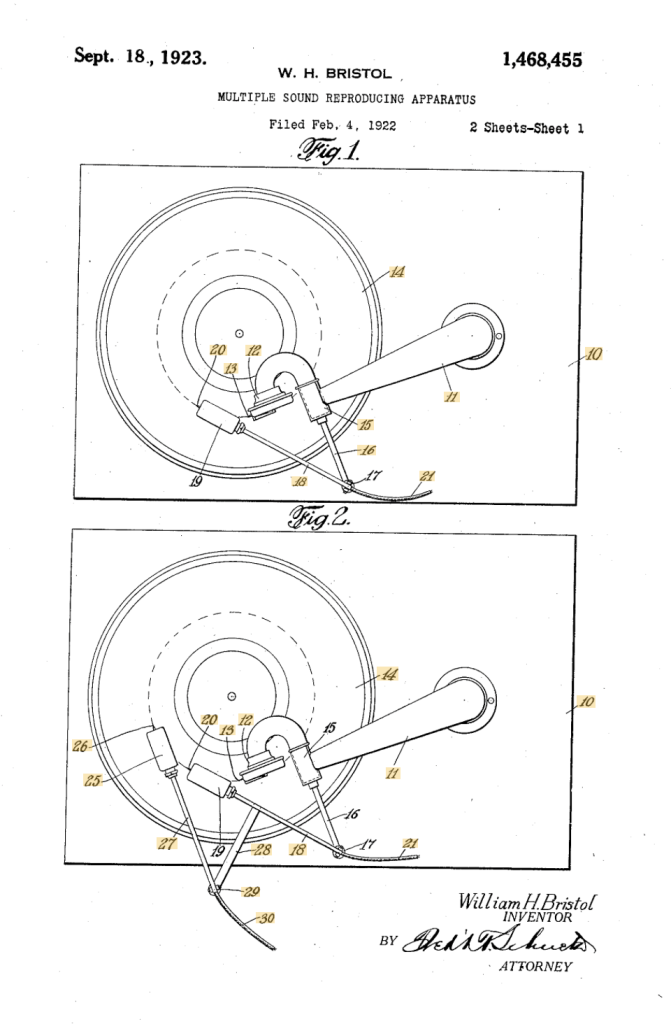

Let’s back up a little to vinyl records. A groove of a vinyl record is a 90º cut, with the needle resting gently on both walls of that trough. If the left wall moves up and down (on a 45º angle to the surface of the vinyl) then the needle bounces up and down with it, but only for that left channel. In other words, it slides along the right wall of the tough.

When a signal is the same in the left and right channels on a vinyl record (the M-component, like the lead vocal) then, when one side of the groove pushes the needle UP, the other side drops DOWN. This means that the M-component signal results in the needle moving horizontally (or laterally), in parallel with the surface of the disc. Signals in the S-component (when the Left and Right channels are ‘out of phase’) result in the two walls moving upwards and downwards together, pushing the needle vertically.

The reason for this is that the old mono shellac discs used laterally-cut grooves, and the reason for this was (apparently) that Emile Berliner was getting around a Thomas Edison patent. Also, by making the needle sensitive to lateral movements, it was less sensitive to vibrations caused by footsteps, which primarily cause the gramophone to vibrate vertically. When they made the first two-channel discs, it was smart to make the format backwards-compatible with Berliner’s existing gramophones.

So, if you have a lot of level and a lot of low-frequency content in the signal on a vinyl record, it causes the needle to jump up and down, and it will likely get thrown out of the groove and cause the record to skip. This is why the bass on vinyl records has to be monophonic, even though the record itself is two-channel stereo. Mono bass causes the needle to wiggle left-right, but not up-down.

So, the historically-accurate answer to explain why it’s okay to use smaller loudspeakers for most of the outputs in a modern 7.1.4 system is that we are maintaining compatibility with a format from 1892.