I found this document from Roland, published in 1978. The information in here is still valuable – and presented as an excellent introduction.

I found this document from Roland, published in 1978. The information in here is still valuable – and presented as an excellent introduction.

We attended a concert last week at the Danish Guitar Camp, where Carlo Marchione played a collection of music written for various instruments in the 1700s. One of those pieces was an arrangement of the Adagio from Mozart’s Klaviersonate in B-Major K. 570, which I had never heard before.

As soon as he started, I thought…. waitaminute…. this tune sounds awfully familiar… as a Canadian…

wait… what?

Have a listen to the first 10 seconds of the Mozart, then listen to the first 10 seconds of the Canadian National Anthem. I suspect that Calixa Lavallée might have had the Mozart tune in the back of his head when he sat down to work on Théodore Robitaille’s commission.

Back when I was at McGill, one of my fellow Ph.D. students was Mark Ballora, who did his doctorate in converting heart rate data to an audible signal that helped doctors to easily diagnose patients suffering from sleep apnea.

This article from Science magazine in 2017 talked about Mark’s later work sonifying astronomical data, but I was reminded of it in a recent article on the BBC about researchers doing the same kind of work.

Late-night free-floating anxiety is not a modern phenomenon. One of my favourite descriptions of it is Dorothy Parker’s 1933 short story called “The Little Hours”, published in The New Yorker.

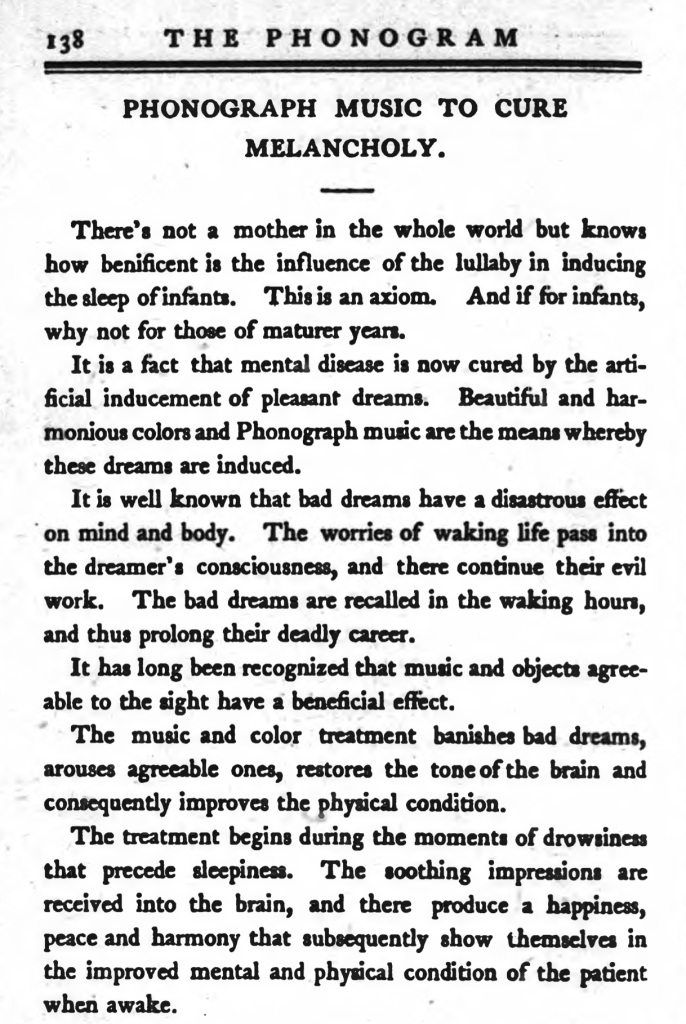

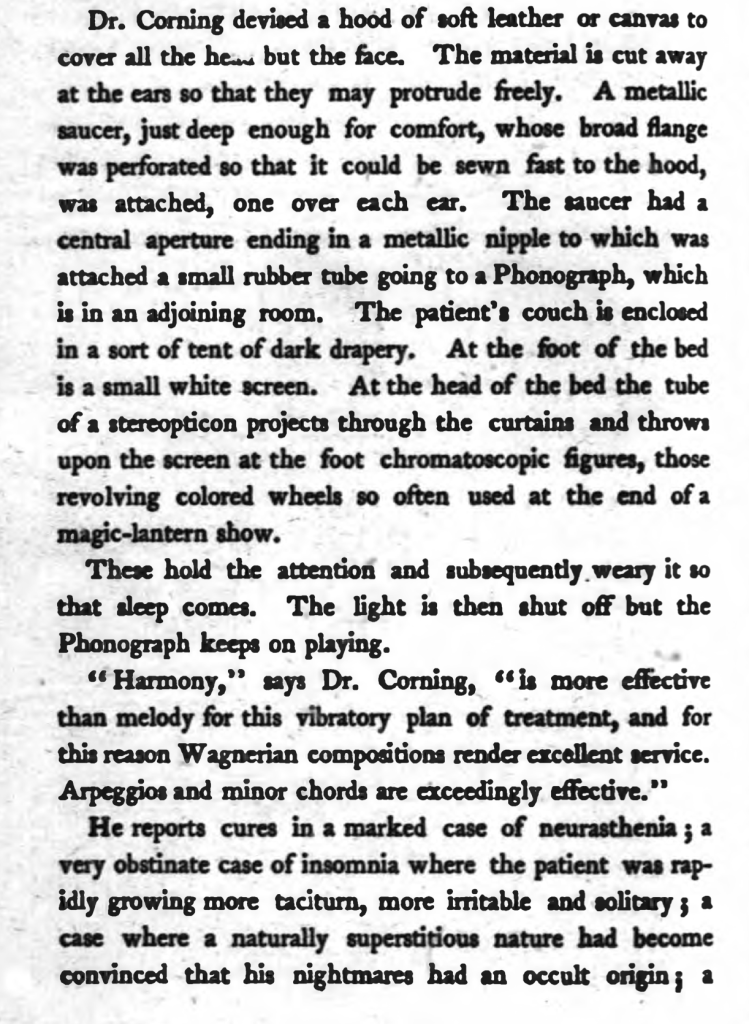

However, more than 30 years before this, The Phono Gram magazine published the following, which a Dr. J. Leonard Corning proposed to cure the problem of late-night melancholy with what we would, today, called a “pair of headphones” (although the design that he describes probably wouldn’t sell well to anyone who is not interested in S&M…) playing Wagnerian arpeggios and minor chords. (Personally, I just put the timer on my iPhone to turn off after 30 minutes, and turn on an old episode of “QI” or “8 Out of 10 Cats Does Countdown” – Sean Lock’s voice drowns out my own internal ones.)

I’ve removed a rather significant portion here…

I live in Denmark where people speak Danish. One interesting word that I use every day is “højtaler” which is the Danish word for “loudspeaker”. I say that this word is “interesting” because, just like “loudspeaker” it is actually two words glued together. “Høj” means “high” or “loud” and “taler” means “talker” or “speaker” (as in “the person who is doing the talking”).

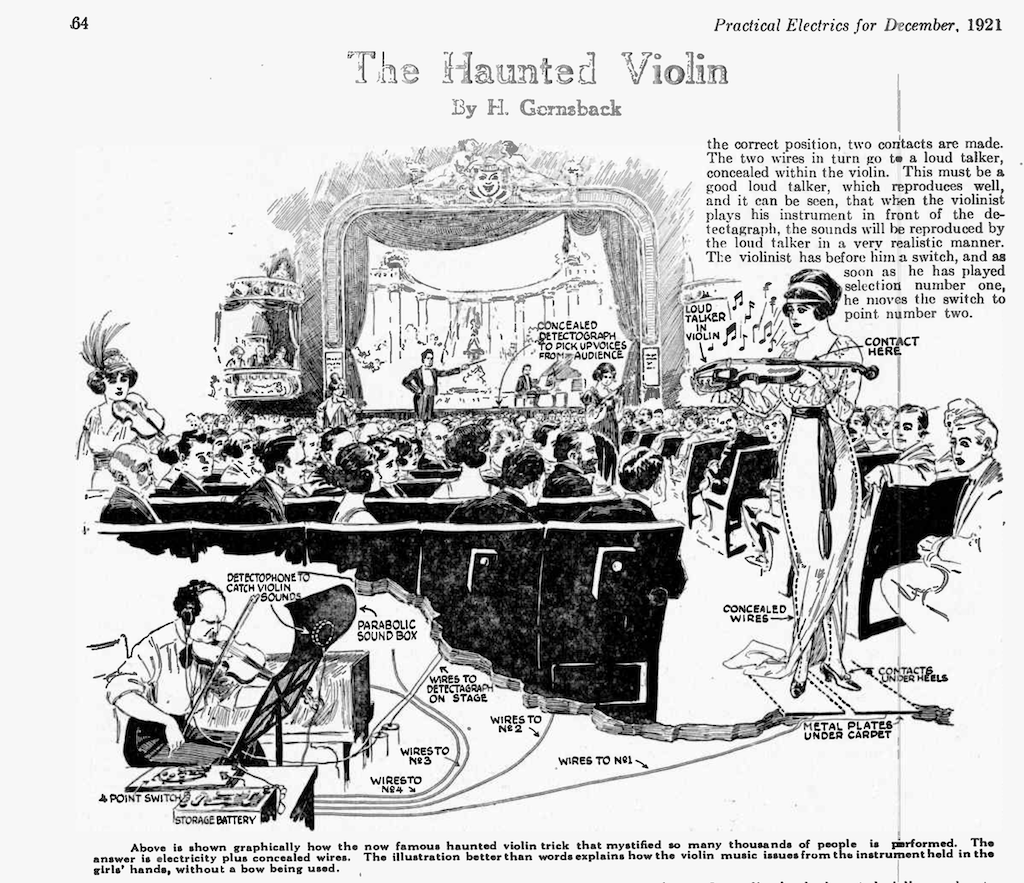

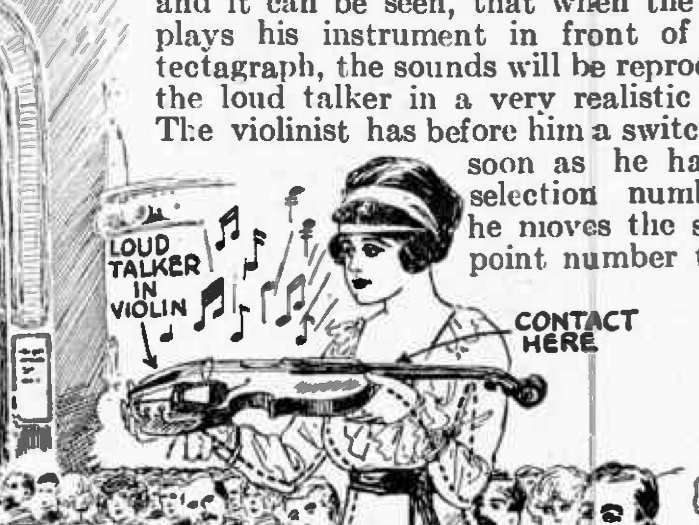

Sometimes, when I have a couple of minutes to spare, instead of looking at cat videos on YouTube, I sift through old audio and electronics magazines for fun. One really good source for these is the collection at worldradiohistory.com. (archive.org is also good!). Today I stumbled across the December, 1921 edition of Practical Electrics Magazine (which changed its name to The Experimenter in November of 1924 and then to Amazing Stories in April 1926*) It had a short description of a stage trick called the “Haunted Violin”, an excerpt from which is shown below.

The trick was that a violin, held by a woman walking around the aisle of the theatre would appear to play itself. In fact, as you can see above, there was an incognito violinist with a “detectophone” that was transmitting through wires connected to metal plates under the carpet in the theatre. The woman was wearing shoes with heels pointy enough to pierce the carpet and make contact with the plates. The heels were then connected with wires running through her dress to a “loud talker” hidden inside the violin.

Seems that, in 1921, it would have been easier to learn at least one word in Danish…

Side note: This is why, when I’m writing about audio systems I try as hard as possible to always use the word “loudspeaker” instead of “speaker”. To me, a “speaker” is a person giving a speech. A “loudspeaker” is a thing I complain about every day at work.

* That April 1926 edition of Amazing Stories had short stories by Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and Edgar Allan Poe!

Post Script:

My wife reminded me that it’s the same in French: “haut-parleur”. It’s a reminder that the original loudspeakers were never intended for music, I suppose…

#92 in a series of articles about the technology behind Bang & Olufsen

One question people often ask about B&O loudspeakers is something like ”Why doesn’t the volume control work above 50%?”.

This is usually asked by someone using a small loudspeaker listening to pop music.

There are two reasons for this, related to the facts that there is such a wide range of capabilities in different Bang & Olufsen loudspeakers AND you can use them together in a surround or multiroom system. In other words for example, a Beolab 90 is capable of playing much, much more loudly than a Beolab 12; but they still have to play together.

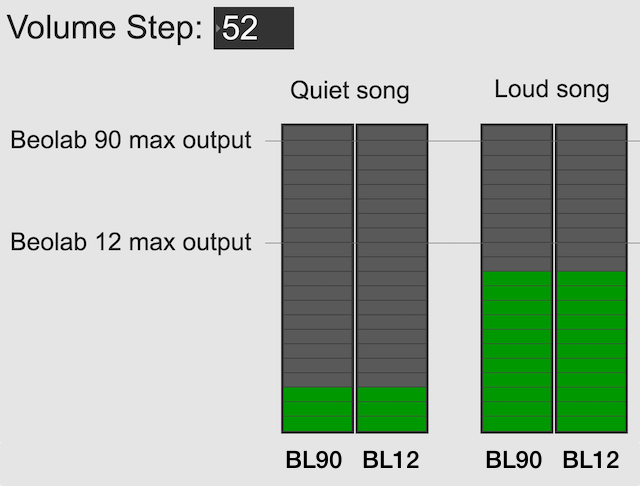

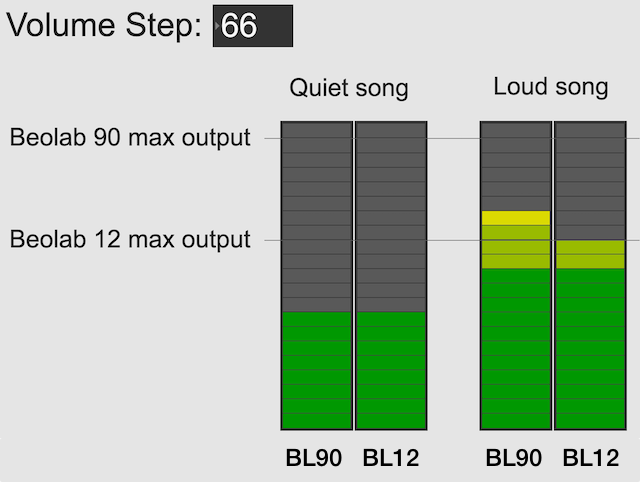

Let’s use the example of a Beolab 90 and a Beolab 12, both playing in a surround configuration or a multiroom setup. In both cases, if the volume control is set to a low enough level, then these two types of loudspeakers should play at the same output level. This is true for quiet recordings (shown on the left in the figure below) and louder recordings (shown on the right).

However, if you turn up the volume control, you will reach an output level that exceeds the capability of the Beolab 12 for the loud song (but not for the quiet song), shown in the figure below. At this point, for the loud song, the Beolab 12 has already begun to protect itself.

Once a B&O loudspeaker starts protecting itself, no matter how much more you turn it up, it will turn itself down by the same amount; so it won’t get louder. If it did get louder, it would either distort the sound or stop working – or distort the sound and then stop working.

If you ONLY own Beolab 12s and you ONLY listen to loud songs (e.g. pop and rock) then you might ask “why should I be able to turn up the volume higher than this?”.

The first answer is “because you might also own Beolab 90s” which can go louder, as you can see in the right hand side of the figure above.

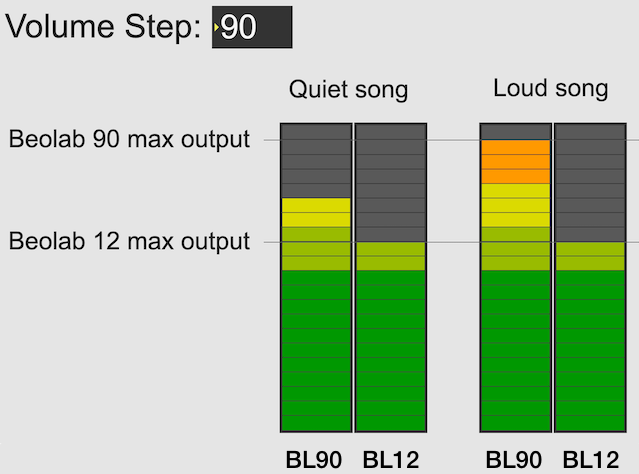

The second answer is that you might want to listen to quieter recording (like a violin solo or a podcast). In this case, you haven’t reached the maximum output of even the Beolab 12 yet, as you can see in the left hand side of the figure above. So, you should be able to increase the volume setting to make even the quiet recording reach the limits of the less-capable loudspeaker, as shown below.

Notice, however, that at this high volume setting, both the quiet recording and the loud recording have the same output level on the Beolab 12.

So, the volume allows you to push the output higher; either because you might also own more capable loudspeakers (maybe not today – but some day) OR because you’re playing a quiet recording and you want to hear it over the sound of the exhaust fan above your stove or the noise from your shower.

It’s also good to remember that the volume control isn’t an indicator of how loud the output should be. It’s an indicator of how much quieter or louder you’re making the input signal.

The volume control is more like how far down you’re pushing the accelerator in your car – not the indication of the speedometer. If you push down the accelerator 50% of the way, your actual speed is dependent on many things like what gear you’re in, whether you’re going uphill or downhill, and whether you’re towing a heavy trailer. Similarly Metallica at volume step 70 will be much louder than a solo violin recording at the same volume step, unless you are playing it through a loudspeaker that reached its maximum possible output at volume step 50, in which case the Metallica and the violin might be the same level.

Note 1: For all of the above, I’ve said “quiet song” and “loud song” or “quiet recording” and “loud recording” – but I could just have easily as said “quiet part of the song” and “loud part of the song”. The issue is not just related to mastering levels (the overall level of the recording) but the dynamic range (the “distance” between the quietest and the loudest moment of a recording).

Note 2: I’ve written a longer, more detailed explanation of this in Posting #81: Turn it down half-way.

This is a radio show by Glenn Gould from 1965 that is the audio version which was expanded by Gould into an article written for High Fidelity magazine’s 15th anniversary edition (which can be downloaded from this site. The article starts on page 46.)